Sun to Cheese: What Does It Mean?

We talk a lot about the "Sun to Cheese" story. We even offer a tour by that name. But what does the phrase mean, and how does sunlight become the tasty cheddar we all enjoy?

1. Harvesting the Sun

Millions of humans eat vegetarian diets, but many plants are only digestible by ruminant animals like cows or sheep. Over eons, people have relied on ruminants to convert indigestible plants into edible, storable proteins: milk, cheese, and meat. We are part of a long tradition.

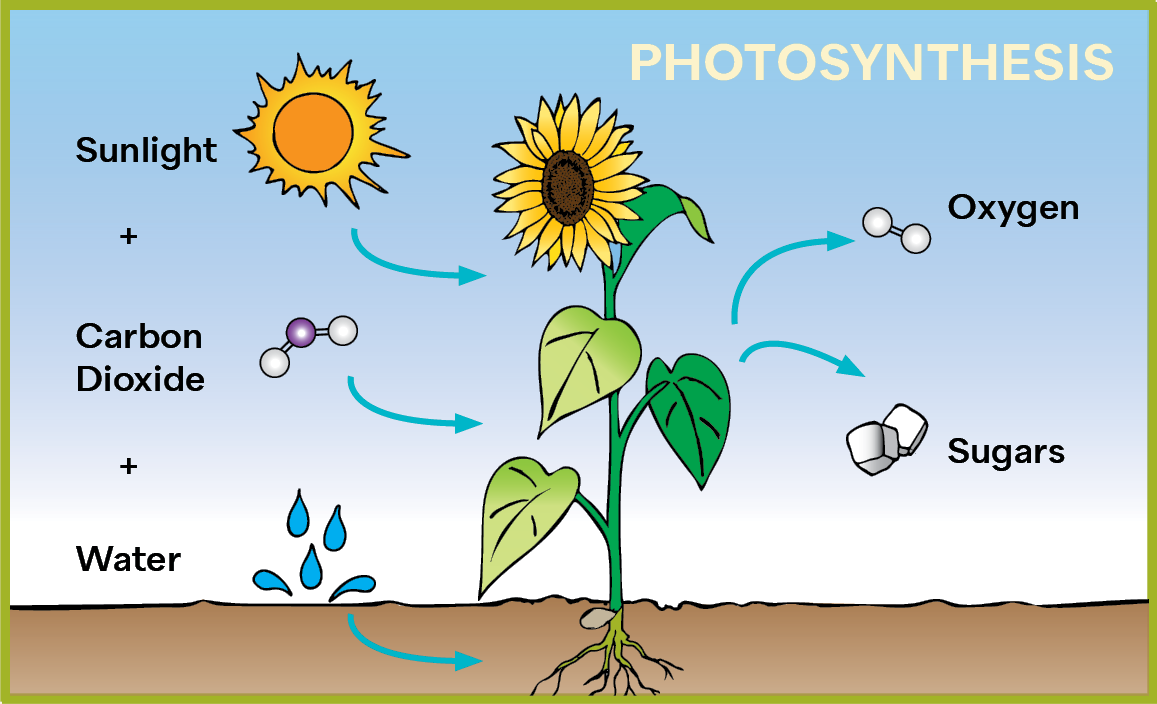

Through photosynthesis, plants store the sun’s energy as simple sugars, which form the foundation of all our food. Photosynthesis makes life as we know it on Earth possible. Talk about a superpower!

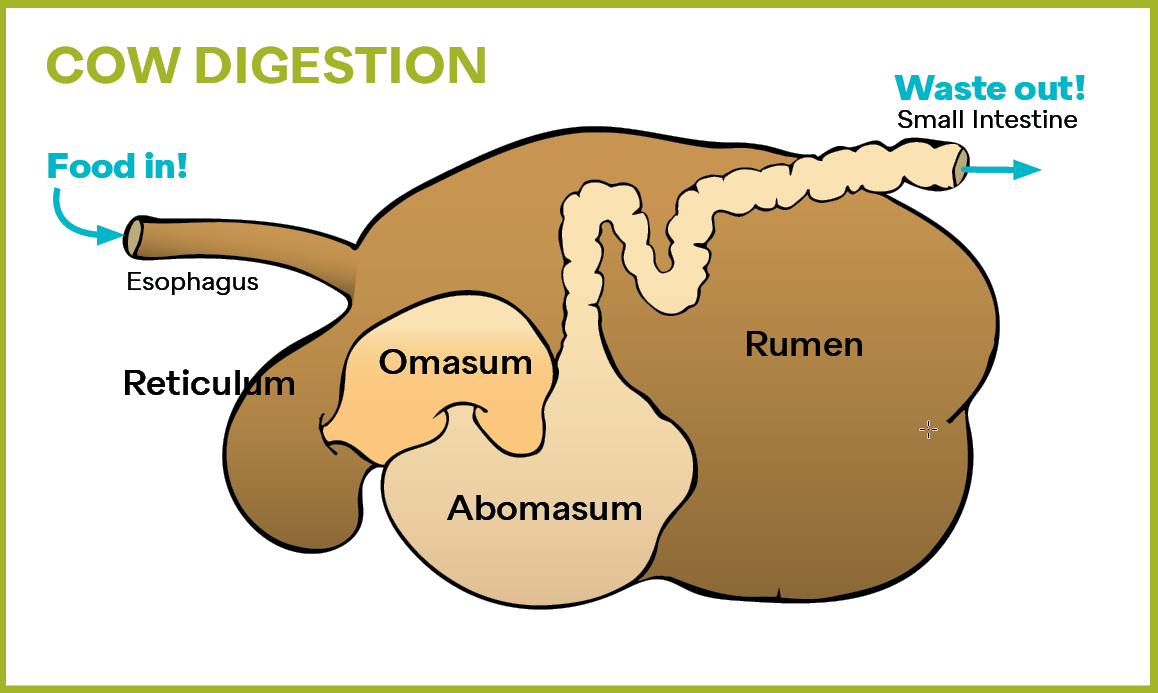

How do our cows take advantage of that? Their special stomachs can digest grass and other plants that we can't.

A ruminant has four stomach compartments. The “rumen” is like a fermentation vat: it’s filled with microorganisms that can break down plant cellulose. (When a cow chews her "cud", she regurgitates softened plant fiber from the rumen and mixes it with saliva to further aid digestion—then she swallows it again!)

But a cow needs a lot of pasture plants—130 pounds a day! So we need to manage our pastures to keep both plants and our cows healthy.

2. Grazing Grass

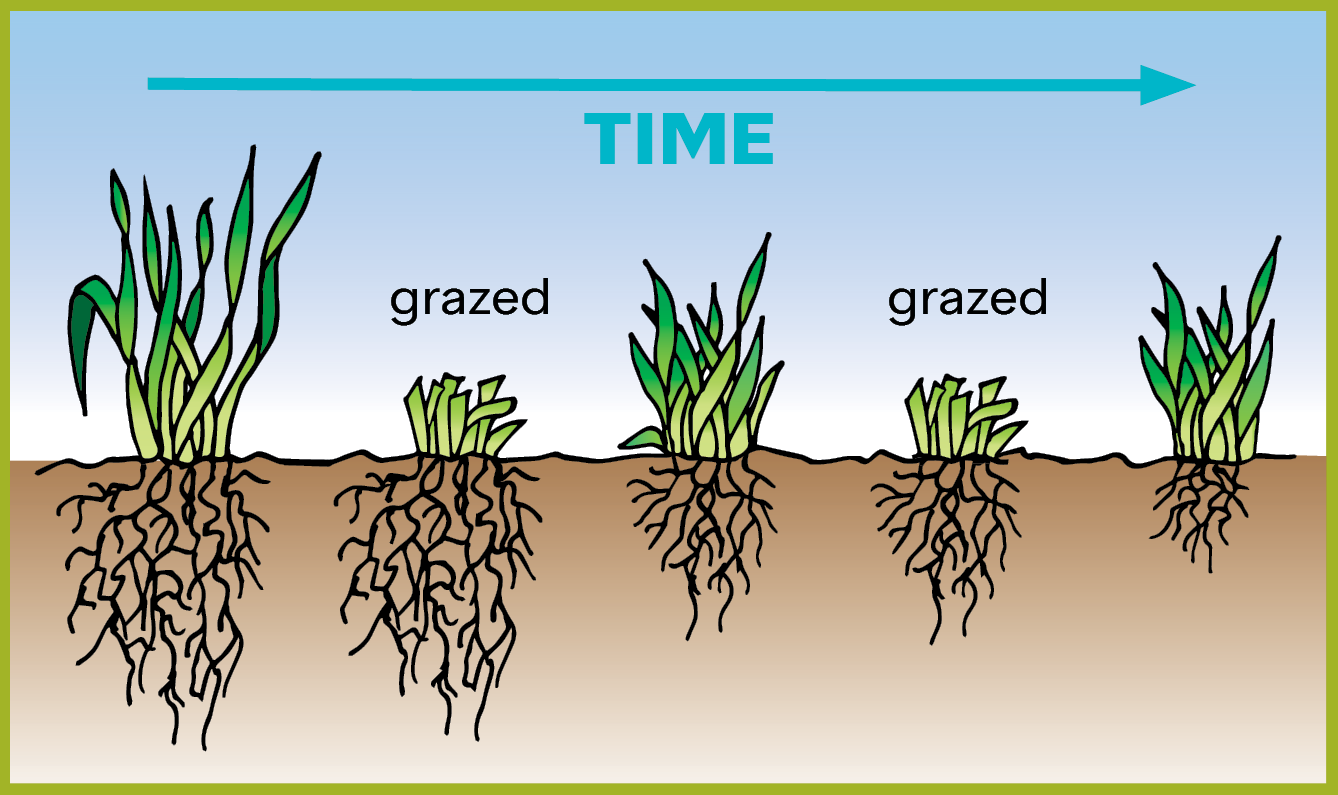

We maintain a nutritious “salad” of pasture plants—a mix of grasses and protein-rich legumes like red, white, and ladino clover—through "managed" or “rotational” grazing. This involves grazing cows briefly but intensively on small sections of fenced pasture. Each section is then given time to regrow before it’s grazed again.

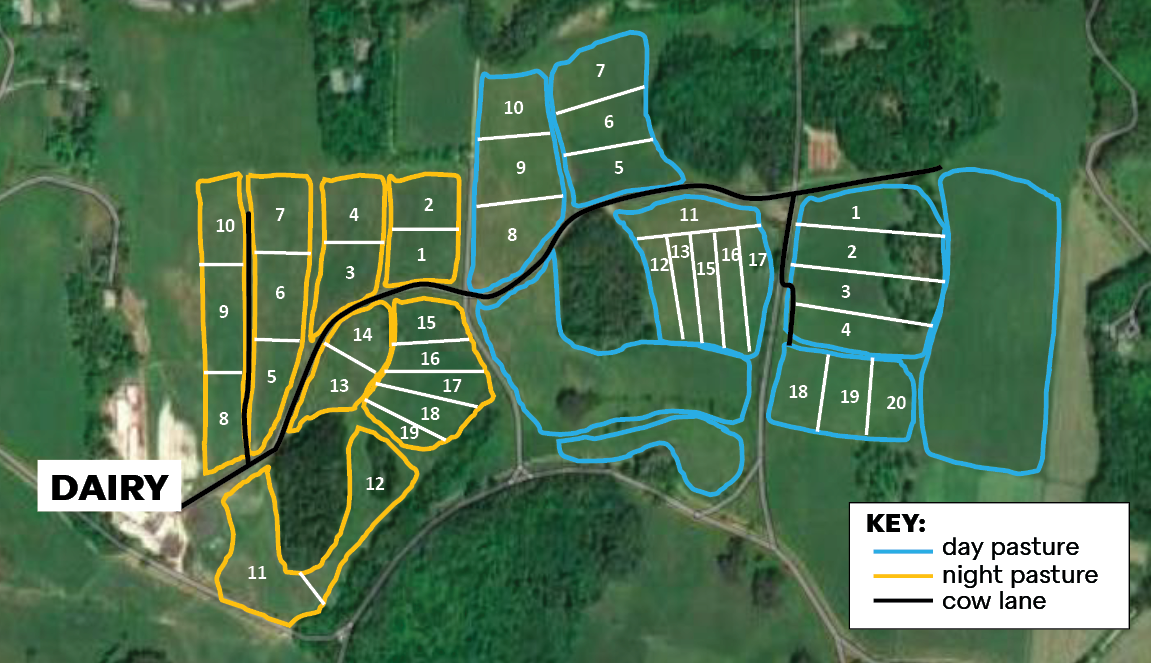

During peak grazing season, we move our milking cows to a fresh strip of pasture each day and night, after each milking. For animals with lower nutritional demands (immature heifers, nonmilking “dry” cows, beef cows, and sheep), we use a variety of grazing rotations.

With managed grazing, the land and animals support each other: the cows fertilize the plants; the plants nourish healthy cows; and a web of roots enrich the soil and store carbon.

In addition to pastures, we mechanically harvest 600 acres of fields to store feed for winter (see our Haying 101 blog), and supplement that with purchased non-GMO grain.

It all adds up to great nutrition for cows to make... milk!

3. It's A Cow's Life

Like all mammal moms, a dairy cow makes milk to feed her babies. So every cow has to have a calf in order to give milk. Over centuries, dairy cows have been bred to make a lot more milk than their babies can consume. We use the rest.

Each dairy cow is bred to have a calf annually. She makes the most milk right after calving and the least toward the end of her lactation cycle. We stop milking her to let her rest at least two months before she calves again. Our average cow has a calf every 13.5 months.

The nutrient-rich “colostrum” milk that a cow produces right after giving birth is not used in cheesemaking. It is fed to her calf to help strengthen the calf’s immune system and give it a healthy start in life.

4. Milking It

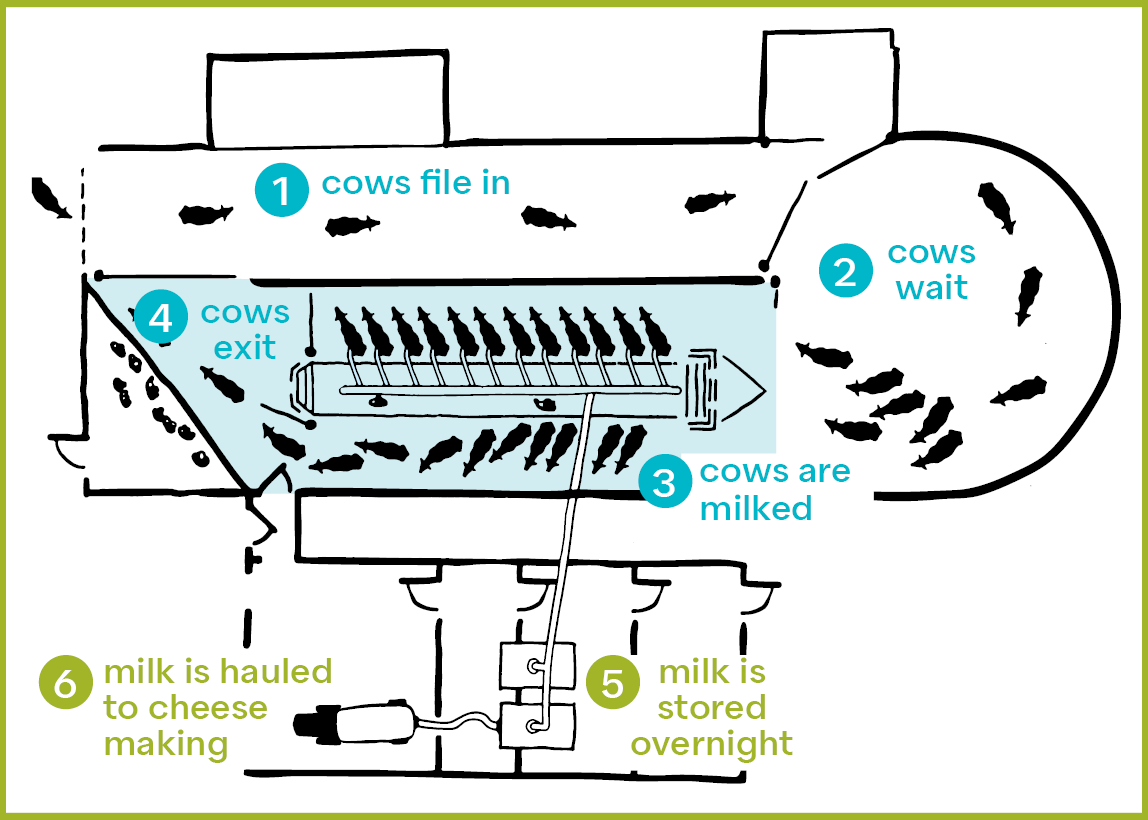

Our staff milks the cows twice a day, at 4:30AM and 3:30PM.

At each milking, 12 cows at a time file into the parlor and line up with their rears facing a recessed pit. From the pit, the milker preps each cow. She carefully checks each cow’s udder to make sure everything looks healthy, then disinfects each teat with a paper towel (one per cow) before attaching the milk machine.

It takes 5-7 minutes for each cow to be milked.

As that's happening, 12 more cows file down the other side of the pit to be prepped. When a cow from the first group finishes milking, the machine is “swung over” to a cow on the other side. Once one side is done, they’re released and a new group files in.

Cows like routine, so they move through the parlor readily, guided by the milker, who also controls manual gates to help usher cows in and out.

The milker can milk about 100 cows in two hours.

Each morning, a cheesemaker retrieves the milk from that morning and the previous evening. It’s a chance to hear from the dairy staff about how the cows are doing, and get any updates that might impact cheesemaking.

So there you have it: From sun to cheese! (Making cheddar is a related story you can read about.)

5. Farming's Future

We believe livestock play a valuable role in sustainable food systems, but we are always asking, "How can we do better?"

We're proud to be a grass-based dairy since the early 1990s. Prioritizing pastures over grain to feed our cows means using fewer inputs and resources. The permanent pastures protect water quality, and our constructed wetlands help absorb manure nutrients directly from our barns and parlor.

So what does “better” look like?

As we aim to achieve net zero here by 2028 (capturing more greenhouse gases than we emit), we’re joining partner organizations to experiment, adapt, and research climate solutions at the dairy, where cow burps and cow manure emit greenhouse gases, mostly methane.

Managed grazing: Our pasture sod and root structures store carbon and will help absorb intense rainfalls, but could they store more carbon?

Diet: We’re feeding our cows a linseed-based supplement and looking into encouraging high-fiber pasture plants to try to reduce methane emissions.

Silvopasture: We’re planting trees in pastures to store more carbon (also grazing cows among existing stands). But trees don’t grow overnight.

Manure management: Can adding biochar (a charcoal-like substance) to liquid manure reduce greenhouse gas emissions?

Where does your food come from? How is it grown? Who makes it? Understanding food systems is critical to shaping the future of farming. Our dairy—and entire farm—prompts students to ask questions like these. By seeking and learning the answers, they’ll help build the sustainable food systems of the future.

This story is based on the Sun to Cheese Exhibit in our cheese viewing area. Come visit it yourself, mid-May to mid-October.